Disclaimer: the writer of this journal fully acknowledges the ethical and moral dilemma of the subject matter in question. This is an “exercise” to explore ways by which it can be replicated, in the event that policy makers consider the shortfalls of this social engineering tool as a lesser evil than the trap of poverty.

By KWAME MARFO

2007 marked the first time in human history that people living in cities and towns outnumbered those in rural areas (UN Habitat, 2007). Rural-urban migration has had a drastic impact on the already creaking infrastructure in urban centers in many developing countries, contributing to high incidences of crime, poor sanitation and other like vices and correspondingly, poverty. This is on an upward trajectory. Fukuyama’s (2007) assertion that history has come to an end and there is no alternative economic and political model other than democratic capitalism does not hold water when put to a critical test. The western approach to solving migration problem in the south has so far yielded dividends. While policy makers, academicians and lay people fret over ways to fix this broken system, the answer lies closer than meets the eye.

China’s migration control apparatus, hukou provides a flawed, albeit compelling template. Criticisms of the system have been manifold, some of the most vociferous of which includes the notion that what works in China may not work in India or Nigeria. This is disingenuous, to say the least. The plausibility of this system or variations of it has been under-explored. For example, from 1983 to 2004, there was one book from an official hukou representative describing how the system works and equally, few scholarly books discussing the system (Wang, 2005).

My objective in this essay is to lend a voice to the limited volume of literature that advocates for this proven system, confront its criticisms and suggest ways by which the current system can be improved and replicated in other developing countries.

UNDERSTANDING HUKOU

According to Georgia Institute of Technology’s International Affairs Professor, Fei-Ling Wang (2005), hukou zhidu or huji zhidu (household registration system) was formally formed in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in the1950s. It is slightly different from earlier versions of institutional exclusive tools that have been used to organize Chinese peoples for social control and tax purposes for over several millennia. The reformed hukou is more comprehensive and rigidly enforced system that ‘divides and organizes people based on locational and family-based differentiation as recognized and determined by the state’ (Wang, 2005, 32).

There are several misconceptions about the system that is worth pointing out. At the heart of hukou is the intent to guide migration and not restrict it, even though in practice, that has not always been the case (Aziz et al, 2006). This is evidenced in the way it has been liberalized on case basis, to allow labor to move into sectors where they are needed. Also, hukou is not a birth right per se. There is room for social mobility such as passing the entrance examination for graduate school which gives any citizen national mobility (Wang, 2005).

ARGUMENT AGAINST HUKOU

The grievances against this system, the ‘unfair treatment and naked exploitation of the excluded population’ (Wang, 2005, 25) raise troubling moral, legal and ethical considerations. They are well-documented. Glossing over it uncritically would be morally indefensible and academically dishonest. On the other hand, harping excessively about it adds little value to finding solutions to the equally morally repugnant plight that bedevils many slums in the developing world. Rather, I will focus on the under-explored merits to the system which I believe offers some solutions akin to the biblical ‘stone which the builders rejected, becoming the chief corner stone’ (Matthew 21:42).

ARGUMENT FOR HUKOU

Economic development

Nobel Prize Economist Sir Arthur Lewis (1983) argues that rapid capital accumulation is central to economic development. The exclusionary principles of the hukou leads to an easier and faster accumulation of capital in the urban sector and in the hands of the state through ‘massive extraction of value’ from rural population (Hu and Yang et al., 2000, 294-295, Shaoguang Wang, 2001). Unlimited movement of labor into cities will not only stifle the accumulation of capital but also drain it as scarce resources would have to be spent to accommodate the interests of the still unproductive migrant labor force (Wang, 2005).

Unless vast amounts of industrial jobs are created to absorb them in order to reduce supply and subsequently, increase wages above the subsistent level, a developing country will be trapped in perpetual poverty. Accumulated capital is needed to create these industrial jobs and hence the argument for hukou (Hu and Yang, 2000). The problem of low wages is also further exacerbated by influx of migrant labor from remote areas which effectively pulls down the wages of the urban areas (Lewis, 1966). Europe in its early development phase circumvented this painful phase by exporting a sizable number of its inhabitants to new found territories in the Americas, Australia and surrounding areas and thus, prevented wage levels from falling (World Bank, 2002). Hukou ‘allows needed talent and labor to move but stabilizes the nonproductive labor for as long as possible. It also creates sociopolitical order and a desirable urban environment to attract foreign investors. This way, modern industries can develop rapidly in the urban sector, quickly lifting the nation as a whole from poverty. The dual economy continues, but the less developed and the excluded sector will gradually shrink’ (Wang, 2005, 19). This issue is not lost on the Chinese leadership. Li Yining (2001) acknowledges this dilemma and argues that a developing country like China has two gaps to close: between itself and the developed world and within its regions. Unfortunately, it can only do one at a time. Thus, the need to focus on closing the gap between China and advanced economies. Once that is achieved, bridging the gap domestically could be achieved with considerably less effort.

Reversal of capital flight

Wang (2005) points out that a protected and prosperous elite, as unpalatable as its sounds, serves a useful purpose. If domestic sources of capital is insecure and unprofitable, foreign capital needed to create high paying industrial jobs tends to be speculative, scarce and runs the risk of being yanked out at the first sign of trouble. The artificially created havens of tranquility and profitability in Chinese cities by hukou attract long term foreign capital. The results have been staggering. China has become the second largest recipient of FDI after the US since the mid 1990s (Chris Giles, 2002). As of 2003, China has attracted more than half of all FDI in developing countries (Yasheng Huang, 2001)

The fiercest critics of the hukou ironically have come from the west. Wang (2005, 123) however, points out that hukou is no different from the Westphalia international political economy that has been in place since the end of the Middle Ages. This system created a ‘political division of sovereign nations, a citizenship-based division of humankind, and exclusion of foreigners’. It led to the development of the modern capitalist market economy that brought economic growth and technological sophistication to OECD countries. China’s prosperous cities on the eastern seaboard, compared with the rest of the country, for all practical purposes, can be viewed as the equivalent of OECD nations, relative to the rest of the world. With that said, the citizenship-based institutional divide between the OECD nations and the rest of the world is much more ‘rigidly defined and forceful, hence more effectively enforced than hukou’. Wang (2005) also highlights that the Chinese central government makes provisions for the reallocation of resources from core to periphery areas, making hukou ‘humane and more tolerable to the excluded than the Westphalia system’.

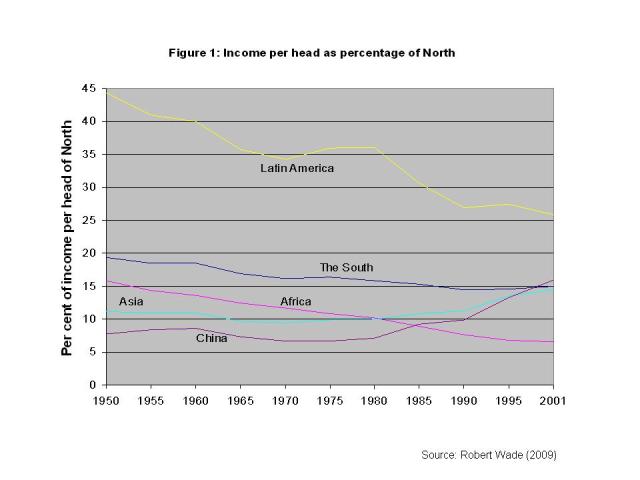

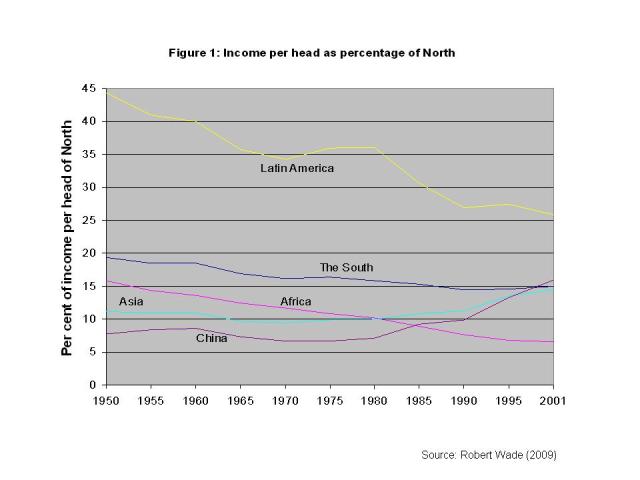

Despite the professed virtues of orthodoxies of the north’s best practices, most indices of human development indicate that China has bridged the development gap while the rest of the developing world has actually retrogressed (Wade, 2007). China has accomplished this mission without following the mandates of the “enlightened west”.

POLICY PRESCRIPTIONS

Whichever side of the divide you sit, one fact is unmistakable; hukou works and thus, the need to examine whether more humane forms of it are replicable it. I will explore this in two fold: 1) strip out the negative components of the current system and, 2) examine what China is doing right and how to replicate it in the periphery states. Implications of these prescriptions will militate against the moral and ethical issues, make the system less unwelcoming and more acceptable and lastly, make it run more effectively.

On its negatives, there are elements of the system that do little to add to the integrity of the stated goal of economic development and subsequently trickle down effect of reducing poverty and addressing social issues. These include and are not limited to the following:

Perpetuation of elitism

In an otherwise robustly stratified system, college education for example provides an escape route to social mobility (Wang, 2005). Unfortunately, the Ministry of Education (2001) rules mandate that college applicants must take their entrance examinations and be admitted in their own local hukou zones. The numbers are heavily skewed in favor or urban areas. For example Beijing, with a permanent population of 10 million has an allocation of 25,000 spots whereas nearby Shandong province with almost 100 million only people gets roughly 80,000. While there is merit on economic and social grounds in granting urban dwellers temporary privileges as the argument for hukou goes, opportunities that grant access (such as education) to the urban hukou ought to be equitable. Granting urban citizens additional preferential treatment despite their enhanced socio-economic advantages at the expense of rural dwellers is unconscionable. If anything, high potential rural dwellers should be given preferential treatment in much the same way that disadvantaged minorities are treated via “ffirmative action” programs in the US to level the uneven playground.

Blatant human rights abuses

In its zealousness to make the system work, the Chinese government sometimes goes overboard by targeting individuals who express legitimate grievances about the unfairness of the system (Wang, 2005). Again migrant workers who lose their jobs are subject to punitive measures including detention. Such outcomes are not only brutal but also counterproductive as they can undermine the legitimacy of the system.

These are examples of bad practices that have been developed overtime, are deeply entrenched and would take considerable effort to do without. In advocating for a type of hukou system to be replicated in the south, we have the benefit of hindsight to learn from China’s mistakes so as not to repeat them. Laws should be rigorously tested frequently by an independent body including outsiders to ensure that they stay true to their stated goals.

On the positive side, I will elucidate features of population control that has enabled it to work in China in an efficient manner. These include but are not limited to the following;

Organization

Officially, the hukou system is defined as a population and social management tool (Jiang Xianjin et al. 1996). China has created huge bureaucracies to ensure adequate running of the system (see figure 2) helped by a nationalistic notion of building a new China (Aziz et al., 2006). Finally and perhaps most crucially, hukou field officers responsible for citizens are mandated to ‘know every resident in each household down to the details of their financial status, close friends and main relations, physical features, accent and slang use, and personal characteristics and preferences’ (Wang, 2005, 69).

Adoptability

Another component of the system that has aided its effectiveness is its design as a work-in-progress. Wang (2005) highlights that its framework is largely based on sketchy legal foundation and is not even mentioned in the PRC constitution. Secondly, provincial and municipal governments, with the authorization of the central government, have the power to make marginal changes in order to adjust to their local municipalities.

Good communication

Hukou is linked to the Xiaokang project, which aims to create a reasonably well-off society by 2050, quadruple GDP by 2020 from the 2000 level, attain a 7% GDP growth rate and target a 1% yearly shift of labor force from agricultural to non agricultural sector.’ (Aziz et al., 2006, 252-253). This project gains its legitimacy from two sources:i) the goals are realistic given that China has achieved it before in the 20 year period preceding the dawn of the new millennium and, ii) it has been effectively communicated to the Chinese people and hence has popular national support.

Finally, I am cognizant of the fact that political processes in most countries may perhaps hinder this process from taking place. An influential force such as legitimization from international institutions such as the World Bank will be needed to give some credence to it. Unfortunately, such institutions are often in bed with their donor countries whose professed ideological leanings hypocritically ran counter with any versions of migration control. Once again, the answer may lie with China. With the epicenter of the global political economy shifting eastwards, China has a once-in –a life-time opportunity to assert itself on the global stage and design the global social, political and economic landscape in the likeness of its troubled image, nevertheless a very successful one, in the same manner that America did over the last century.

CONCLUSION

Arguments against hukou are very valid on moral, legal and ethical grounds. Having spent a significant amount of my teenage and early adult years in the poverty infested borough of the Bronx, I am hugely aware of the tragic and vicious trap of malignant forms of discrimination borne out of bigotry, ignorance and irrationality. However, I do realize, and have seen the positive outcomes of benign forms of discrimination which is applied as a temporary measure to achieve goals such as correct past failures (e.g. “affirmative action” programs in the US which give preferential treatment in university admissions to disadvantage but promising underrepresented youth of color).

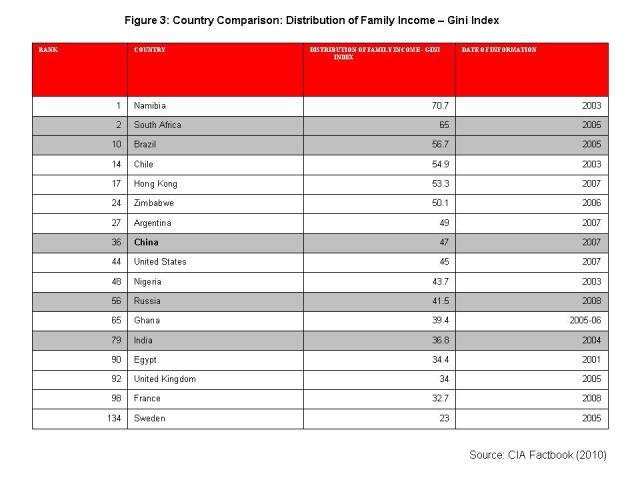

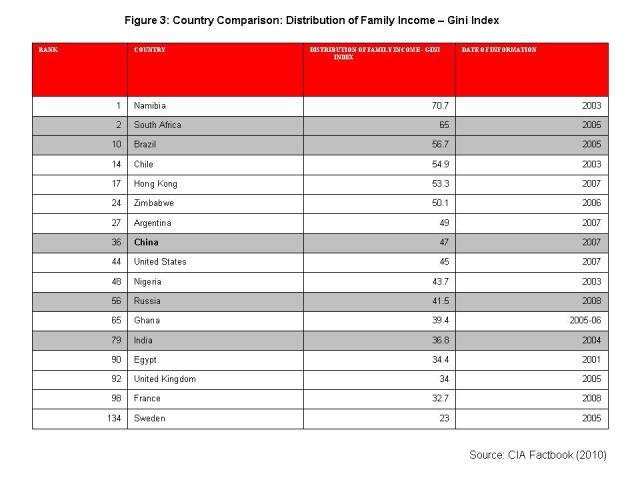

The reality on the ground is most developing countries are caught between a rock and a hard place- accepting moderate but temporary forms of discriminatory practices to cure the curse of poverty (the Chinese model) or perpetual poverty, albeit with piecemeal attempts at poverty reduction (the model for the rest-of-the-developing-world (RDW) model). Let’s not kid ourselves here; the RDW model, as Aziz et al (2006, 251, 255) point out, does not guarantee free movement of labor even if the state leaves it to the market. Rather the demands of social structure (market imperfections such as ethnicity, religion, caste, culture, and linguistic identities) ‘dictate who would leave the countryside and how they would be welcomed or “settled” in the cities’. Despite China’s history with hukou, its Gini index is comfortably stuck in the middle as compared to its competitor countries (better than Brazil and South Africa but worse than India and Russia) (see figure 3).

In summary, ‘a model of economic development assisted by institutional exclusion (Chinese model) is by no means ideal or even fair but realistically, it may be the only way for a latecomer nation to accelerate its growth in the information age with a globally integrated financial market,’ to break the vicious cycle of poverty (Wang, 2005, 20). The challenge is to minimize inevitable negative externalities that may arise in terms of ‘sociopolitical stability and national cohesion’. Insofar as it is a means to an end and not an end in itself, it may, to borrow the words of Wang (2005, 22) perhaps be ‘a lesser but necessary evil’. On the other hand, if policy makers reject my advocacy of this temporary benign form of discrimination that has been adopted by China to attain its developmental goals, as a matter of principle, I cannot, with a clear conscience, take aim at them.

APPENDICES

Copyright 2011 (April) Neo-African Consensus

Copyright 2011 (April) Neo-African Consensus